Agricultural index insurance is a tool for risk management that has shown significant promise for promoting sustainable development and resilience. Index insurance can help small-scale farmers and pastoralists to increase their resilience to weather shocks like drought or flood while encouraging investments in productivity that in good years create a pathway to prosperity.

However, effectively implementing agricultural index insurance has been complicated. Agricultural index insurance interventions require collaboration across multiple public- and private-sector partners. Markets have also struggled with expensive yet poor-quality contracts and inadequate consumer education, resulting in low levels of adoption by individual farmers.

Agricultural index insurance and our understanding of how it can be used as a tool for sustainable development have grown substantially since the earliest interventions took place in the 1970s. A growing body of research suggests that agricultural index insurance will be a primary risk management tool for major resilience-based initiatives that include the G7 InsuResilience initiative, which seeks to extend insurance coverage to an additional 400 million households worldwide by 2020.

The MRR Innovation Lab’s Index Insurance Innovation Initiative (I4) is at the leading edge of research on better agricultural index insurance contracts and interventions worldwide. This article provides a short introduction to agricultural index insurance, including how it works and a window into its significant promise as a risk management tool to promote sustainable development as well as its pitfalls.

How Index Insurance for Agriculture Works

Agricultural index insurance bases payouts on an easy-to-measure index of factors, such as rainfall or average yields, that predict individual losses. Index insurance is attractive as a risk-management tool in developing countries where the fixed costs of verifying claims for a high number of small farms make conventional insurance too expensive.

Agricultural index insurance overcomes two key problems with conventional insurance besides high cost: adverse selection and moral hazard. One example of adverse selection in agriculture is when farmers who are more likely to suffer losses are the only ones who buy insurance. An example of moral hazard would be if covered farmers cut back on effort or compromise yields for the specific purpose of receiving an insurance payment. Index insurance overcomes both adverse selection and moral hazard because the index is based on factors that cannot be influenced by any one person.

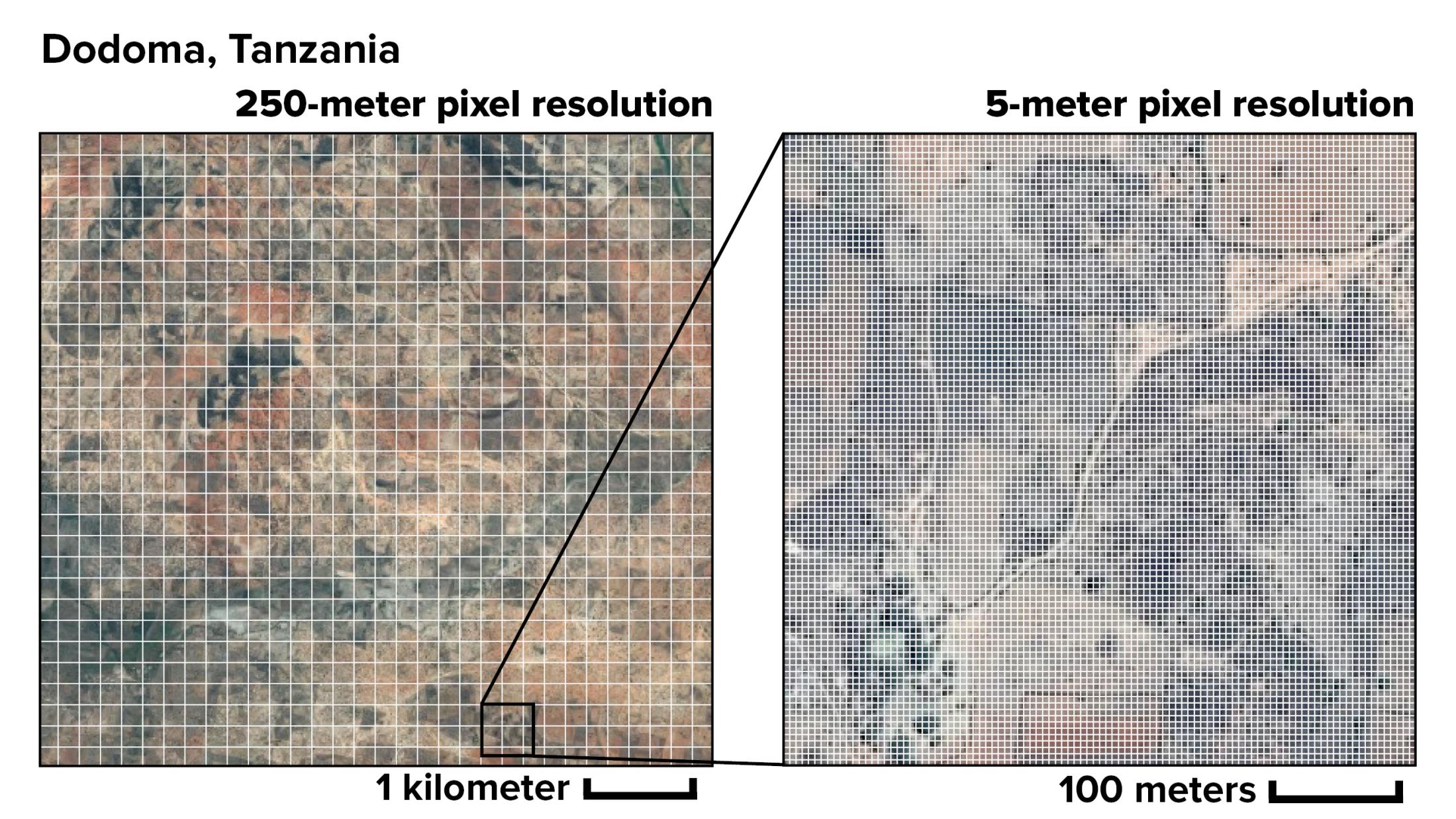

The most common types of indices (plural for “index”) are average area yields, vegetation growth (NDVI) and rainfall. Each of these indices can statistically predict an individual farmer’s crop or livestock losses with varying accuracy and at different costs. While area yield indices have fixed costs that vary depending on how much area is measured, both NDVI and rainfall can be measured remotely, which makes it possible to increase accuracy without necessarily increasing costs.

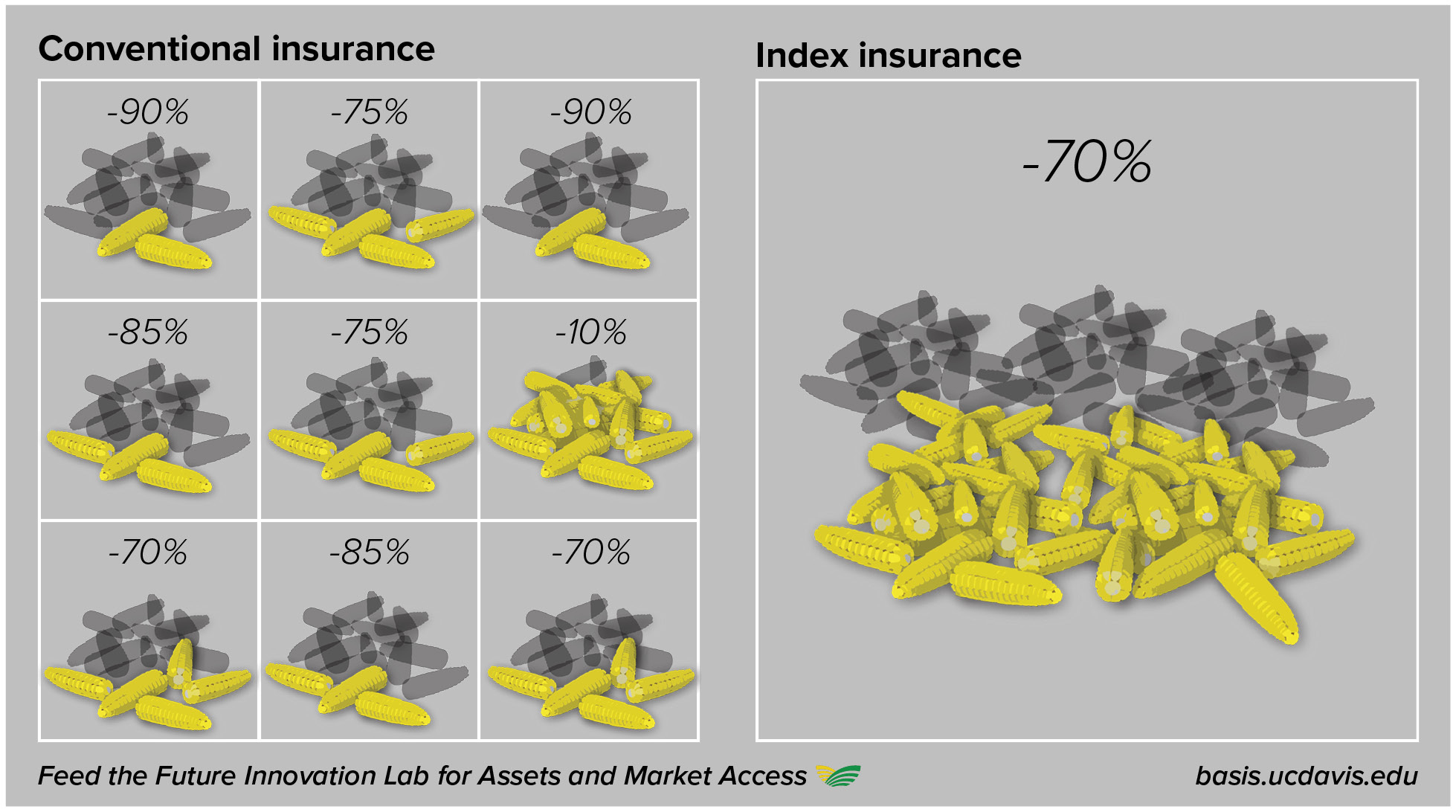

This highlights one drawback to index insurance, which is basis risk, meaning the difference between an index’s estimate of an individual farmer’s losses a farmer’s actual losses. With index insurance there is always the chance that an individual farmer who experiences a loss will not receive an insurance payout. There is also always the chance that a farmer who had a year without any losses will receive a payout. In either case, an index insurance contract has failed.

In a way, basis risk is a tradeoff for avoiding the need to verify individual losses. Index insurance will always carry basis risk, since an index of average conditions in an area will not necessarily capture conditions on each individual plot. One challenge for researchers moving forward is to develop more accurate indices that do a better job of predicting individual losses at lower costs and building better contracts that include failsafes so farmers who receive no payout are still protected.

How Agricultural Index Insurance Can Promote Economic Development

Agricultural index insurance strengthens agriculture in developing countries by acting as a safety net when disasters do occur and by enabling greater investments in productivity. Both benefits together—a safety net in bad years and higher income in good ones—are how agricultural index insurance can have a disproportionately larger impact than other development interventions.

What sets agricultural index insurance apart from other development interventions is how it mitigates risks that act as barriers to investments in productivity. All small-scale farmers and pastoralists insure themselves against weather and other risks. For example, some choose traditional varieties of seeds saved from previous seasons over hybrids that can triple yields but that must be purchased every season.

Limiting investments is one way to limit losses in the event of a catastrophe. The question is just how much these self-insurance strategies actually cost households who are already struggling, and also how much opportunity is missed in order to safeguard a primary source of food. Development economists who study the impacts of agricultural index insurance call increased investments in productivity “ex-ante” effects. These ex-ante effects come from the decisions a farmer or pastoralist makes with the knowledge of insurance coverage.

A small but growing literature is finding that quality agricultural index insurance interventions do have significant ex-ante impacts. A recent intervention among cotton farmers in Mali and Burkina Faso measured just how much the presence of insurance increased investments in productivity. In Mali, the impact was most striking, with an estimated US $48 cost of insurance generating additional cotton cultivation worth roughly $300 at harvest for a cost/benefit ratio of 6.25.

In addition to ex-ante effects, research has shown agricultural index insurance to have powerful “ex-post” effects as a safety net, particularly in the case of the Index-based Livestock Insurance program (IBLI) for pastoralists in Kenya and Ethiopia. First piloted in 2010 by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) with support from the Feed the Future AMA Innovation Lab, a 2013 evaluation found insured households were 36 percent less likely than the non-insured to sell livestock as a way to cope. Insured households were also 25 percent less likely to reduce meals than non-insured households.

Pursuing a Minimum Quality Standard for Agricultural Index Insurance

Despite the rapid recent growth of government and donor investments in its development, not all agricultural index insurance contracts have the potential to leave farmers better off than if they had no insurance at all. The quality of index insurance products available in developing economies is unregulated, putting vulnerable households at an unnecessary risk. Poor-quality products that fail farmers also compromise markets for better products made available later on.

While farmers considering agricultural index insurance have no way to know whether their payments will translate to real protection in the event of a disaster, products with similarly hidden levels of quality already come with third-party certifications. In almost every country, seed companies must submit new varieties to national germination trials for government quality certification. Electrical products like toasters and televisions are globally certified by UL for meeting industry-wide safety standards.

The Feed the Future AMA Innovation Lab has developed a Minimum Quality Standard (MQS) that establishes an objective measure of quality for agricultural index insurance contracts that could be adopted for certifying products worldwide. MQS easily compares the value over time of having an index insurance contract, having no insurance and an equivalent cash transfer.

Beyond establishing minimum quality, MQS can also be used to establish whether an agricultural index insurance contract is a cost-effective means to support farmers’ wellbeing compared to other potential types of support. From the perspective of a donor or government considering subsidies to promote agricultural index insurance, every index insurance contract should have a better dollar-for-dollar potential to stabilize incomes than an equivalent direct cash transfer.

The Future of Agricultural Index Insurance for Development

Uninsured risk for smallholder farmers also affects local and regional economies that depend on the success of agriculture. Effective risk-management tools could help to stabilize small-scale farmers’ livelihoods, promoting broader agricultural and economic growth.

Research and opportunities for more accurate indices for agricultural index insurance have grown substantially, especially in recent years with advances in remote sensing and satellite technology. As indices become more and more accurate, basis risk across agricultural index insurance markets will continue to decline. This could have a major impact on uptake, as research has shown that a central reason farmers choose not to buy insurance is because of its high costs.

Index insurance could also play a significant role in aid budgets increasingly focused on resilience and an end to emergency aid. As the risk of weather shocks is forecasted to increase, national social protection budgets will struggle to keep up with the number of households in need. A recent theoretical study showed that a resilience-based approach to social protection that includes insurance is the only sustainable way to manage and in fact reduce poverty rates in the long-term.

As the frequency and intensity of weather-related shocks continue to grow, so does the risk that more households will live their lives in destitution. This raises the stakes for addressing poverty, food security and vulnerability through resilience-based social protection programs, as the alternative for many families is chronic poverty that lasts for generations.

Keep up with our latest research with MRR Update.