AMA Innovation Lab Launches Project Using High-resolution Satellite Data to Improve Accuracy and Quality of an Innovative Risk Management Tool

Small-scale farmers in developing economies worldwide may soon have better financial tools to manage the risk of drought with a new AMA Innovation Lab project using ultra-high resolution satellite data.

The project will use these measurements of vegetation growth to develop an index for agricultural insurance that does a better job of predicting small farm crop yields. These measurements, taken by a private earth science company’s satellites flying over parts of Mozambique and Tanzania, are 50 times more detailed than those used for current index insurance products. The project is led by researchers at The Ohio State University and UC Davis, and funded by USAID.

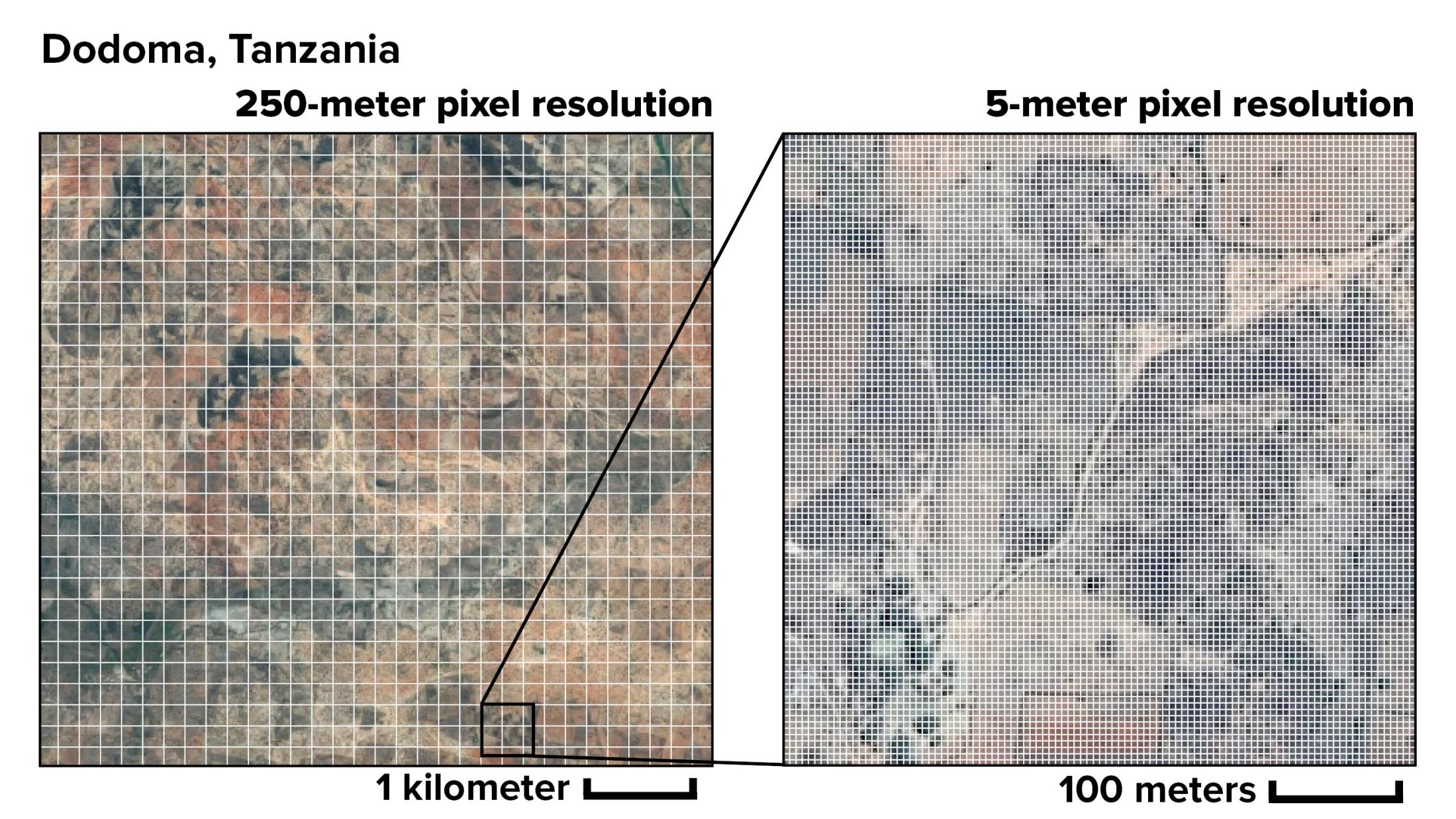

“Right now we’re using the 250-meter level data, and the problem is that farms in sub-Saharan Africa tend to be very small and very dispersed,” said Jon Einar Flatnes, a principal investigator on the project and an assistant professor in the department of Agricultural, Environmental, and Development Economics at The Ohio State University. Flatnes received his Ph.D. in agricultural and resource economics at UC Davis in 2015.

“We’re implementing a training algorithm that will mask out anything that’s not maize crops,” said Flatnes, “and you can do that if you have ultra-high resolution data.”

How Index Insurance Creates a Pathway out of Poverty

Index insurance is an innovative financial tool proven to affordably protect smallholder farmers when they lose crops to drought. Traditional indemnity-based insurance, which pays out for verified losses, does not work for small-scale agriculturalists due to its high costs.

Index insurance avoids these costs by basing payouts on an index of weather conditions based on data from satellites or weather stations, or on estimates of average losses in an area.

“It protects farmers from negative shocks that may force them to take their kids out of school or reduce the amount of food they eat, which can have long-term impacts on their families,” said Flatnes.

AMA Innovation Lab director Michael Carter, a UC Davis professor of agricultural and resource economics and co-principal investigator on the project, said that index insurance also encourages farmers to invest in more productive agricultural technologies. These investments can help many small-scale farmers create a pathway out of poverty and provide security to those who are at risk.

“If you have a quality contract that doesn’t let them down, the hope is that farmers will invest more in technologies like high-yield seeds,” said Carter.

This project is part of a larger AMA Innovation Lab project currently underway in Tanzania and Mozambique in partnership with CIMMYT. “Bundling Innovative Risk Management Technologies to Improve Nutritional Outcomes of Vulnerable Agricultural Households,” is exploring the impacts of pairing drought-tolerant maize seeds with index insurance.

Drought-tolerant seeds can survive without water for longer than conventional seeds, but in an extended drought they could still fail. In that case, index insurance would provide seed replacement for the next season when the cash to buy improved seeds is most likely to be scarce.

Higher-resolution Measurements Can Improve Risk Management

Index insurance is far from perfect, said Carter. Many existing indices are based on satellite measurements of average vegetation cover across pixels of 250 square meters. This could miss a lot of variation within that quarter-kilometer square of land. In developed economies with large, contiguous plots of land dedicated to farming, measurements at this resolution can still accurately predict crop yields.

Developing economies often have smaller and more widely disbursed farm plots that are harder to distinguish from other types of vegetation or non-farm land. In these areas, current index insurance contracts are less effective at predicting crop yields. If crop growth is far below the average across that half-kilometer pixel, the farmer may experience losses but still have no chance of a payout.

“For an insurance product to be valuable, it has to pay farmers when they have losses and not pay them when they don’t,” said Carter. “By getting an accurate prediction for farm yields, you get a contract that works most of the time.”

Public-private Partnerships for Satellite Data and Index Insurance

The project will use data from Planet Labs, a San Francisco-based private earth science company. The data are not publicly available, and were provided to the research team through an agreement with USAID.

Many current index insurance contracts are based on measurements taken from the MODIS instrument aboard NASA’s Aqua and Terra satellites. Planet Labs’ RapidEye satellites are smaller and more specialized, but provide a pixel resolution of five square meters, which is 50 times the resolution of public space agency satellite imaging.

More commonly, said Carter, public-private partnerships for index insurance rely on public funding to cover the large fixed costs of research and development for a tool designed to benefit small-scale agriculturalists worldwide. Covering this initial investment keeps index insurance profitable for private insurance companies despite the small potential market and the ongoing incremental costs.

“A private-sector company would be reluctant to make that initial investment,” said Carter.

Media contact:

Alex Russell, (530) 752-4798, parussell@ucdavis.edu