Q&A: The Business Case to Meet Growing Smallholder Need for Financial Risk Management

For many smallholder farmers, a single drought or flood can destroy their livelihoods. Today, microfinance institutions and insurance companies provide different tools to manage these risks. While these products can transform the lives of people who use them, does that assume providing and investing in improving them is good for business?

Tara Chiu, associate director of the MRR Innovation Lab has worked with numerous insurance companies and microfinance institutions to test various financial risk-management tools around the world. In this Q&A, she outlines some of the key ideas that underpin a powerful business case for insurance companies and microfinance institutions to invest in the future of risk-management tools for smallholder farmers.

Index insurance and other risk-management financial tools are touted as potentially transformative for rural families, but how does the private business sector benefit by making these tools available?

The most obvious benefit goes to insurance companies because they’re expanding their market and, if they offer quality products that work, increasing trust to other kinds of insurance. Understanding insurance as a concept can often be difficult for farmers. We have discussed research showing that when farmers receive a payout that matches their prior understanding of how insurance should work, it can lead to them buying insurance year after year instead of dropping it the first year they don’t get a payout.

Commercial banks benefit due to increases in credit repayment. A lot of commercial banks are not able to offer insurance because of national regulations, so they might collaborate with insurance companies to expand and maintain customers who might otherwise drop out after a shock. In fact, insurance may also encourage farmers to take on more loans. We supported research in Ghana that found that depending on how the payouts were disbursed, insurance increased credit applications from women by as much as 17 percent.

There’s also an incentive for other private sector companies like major input dealers and seed companies to sustain or even expand their clientele by investing in risk manage tools. Input dealers experience client losses when the technologies they offer, like drought-tolerant seeds, fail in extreme events.

Serious shocks can lead to farmers being discouraged about those kinds of technologies even when the products have inherent limitations. Drought-tolerant seeds are not drought-proof. They were bred to handle moderate droughts, but if those crops fail because of extreme events people stop buying the seeds in spite of their benefits. We have worked with seed companies to bundle stress-tolerant seeds with insurance. We have found that clients feel they get more protection from the bundled and respond by investing more in productivity.

Another kind of private sector partner that stands to benefit is a large commercial off-taker that works with contract farmers. Instability of supply chains caused by severe risks to farmers can threaten a consistent supply. Financial risk-management tools like insurance create an opportunity for commercial off-takers to create a stable supply chain. In addition, if they are looking to expand the production of higher-value crops that are more exposed to climate risk, financial risk-management tools could increase farmers’ investments like they did in one of our projects in Burkina Faso’s cotton supply chain.

What about profitability? How can making these tools available strengthen a company’s bottom line?

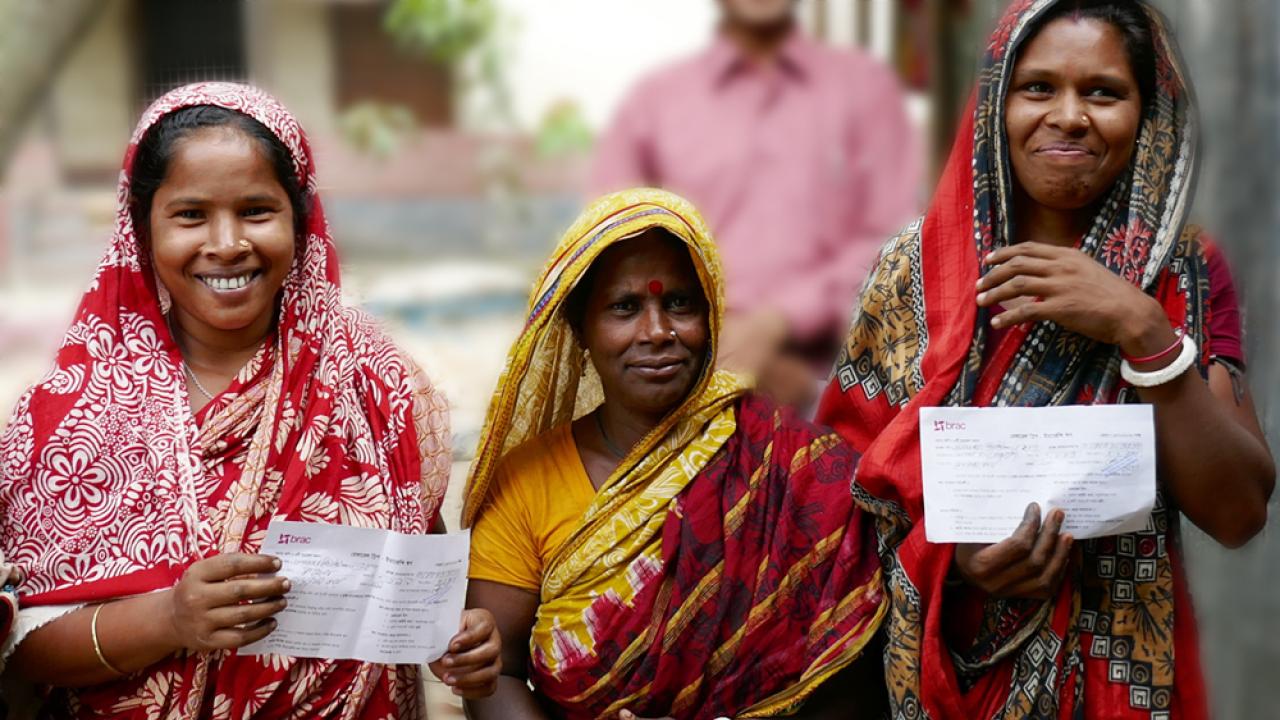

This is something that’s been under-observed, and there is a lot of potential for more research in this area. One example is research we supported that developed and tested a contingent line of credit with BRAC in Bangladesh. It’s a line of credit that becomes available in the event of an indexable shock. In Bangladesh the index was based on flooding.

One of the things the researchers found in that study is that the per-client profitability of microfinance branches that offered this kind of loan actually increased compared to branches that did not. What’s particularly interesting is that borrowers who were closest to the cutoff in terms of creditworthiness took the most advantage of this loan. Expanding this kind of loan to these borrowers, rather than limiting them to more established borrowers, is potentially a huge opportunity. A financial institution to expand their client base of people who can increase their reputational assets with them over time.

A contingent line of credit requires a lot of trust in the borrower, so it’s also ideal for maintaining the institution’s best borrowers who will remain trusted clients unless there is a shock that causes them to default. When a lender offers a line of credit in a moment of crisis, what actually happens is that people have the means to stay in good standing. In the end, keeping clients financially stable increases a lender’s long-term profitability.

What are the major challenges for improving the reach of these financial instruments in ways that secure rural livelihoods while also helping the companies that provide them to grow?

What needs more discussion is the quality and reliability of index insurance products available to farmers. We developed the Minimum Quality Standard (MQS) for index insurance for exactly this reason. MQS is a way to provide transparency across the insurance industry but also for farmers about the index insurance products on the market.

With the same data needed build an index insurance product, we can calculate the likelihood it will fail to pay accurately. Further, we can predict whether those failures cause additional harm if they happen in a particularly severe shock.

Passing MQS means that at a minimum, an insurance product is statistically unlikely to leave a person worse off for having bought it. An MQS analysis also shows why a product fails, which provides guidance on improving it even if it’s actively on the market.

We talk a lot about insurance quality from the perspective of farmer welfare, and that part is critical. But quality is also very much in the interest of the companies that offer these products. If a company sells a low-quality product that fails to release payments after a major shock, people will quickly get disillusioned about agricultural insurance in general.

Say another company enters that same market with a high-quality tool, people won’t buy it. The actions of a single company with a low-quality product can ruin the market for everyone else. Because of this, there’s a common stake in making sure that index insurance products everywhere meet at least a minimum level of quality.