Productive asset transfers are a popular method of alleviating poverty among rural families. Heifer International is a historical leader in productive asset transfers paired with transfers of human and social capital in an effort to help the rural poor, particularly women, achieve a stable, independent and growing income.

From 2014-2018, we conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the impacts of Heifer International’s Smallholders in Livestock Value Chain (SLVC) program approach to development in rural Nepal that bundled a productive asset transfer with extensive context-specific training to empower rural women to achieve sustainable exits from poverty.

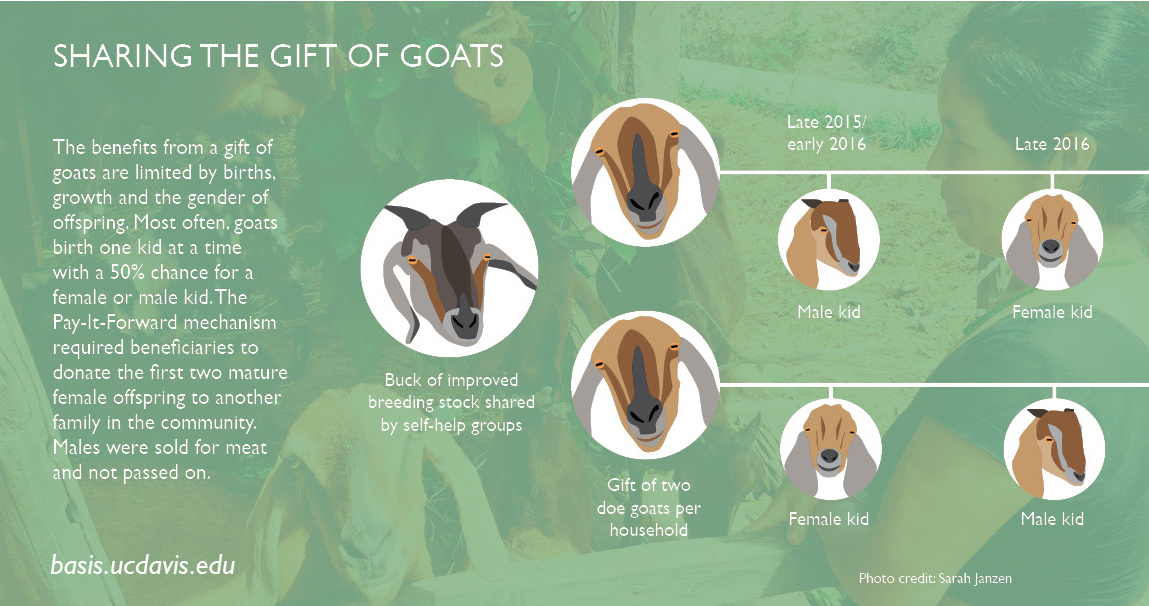

The program provides goats as a productive asset, values-based trainings, support to form self-help and savings groups as well as technical trainings on improved animal management and entrepreneurship. Each participant receives two female goats and each self-help group (SHG) receives a male goat of superior breeding stock.

The values-based training instills the practice of recruiting, training and giving an asset to others in the community. This “Pay-It-Forward” (PIF) mechanism, an essential feature of all Heifer International livestock transfer and training programs, is intended to quickly extend the program to second-generation PIF beneficiaries that includes family in the community.

Our study, the first large-scale RCT of a Heifer International program, evaluated the impacts of the two key components of the SLVC approach separately– the asset transfer and the PIF mechanism – both for initial and PIF beneficiaries. Unpacking the impacts of core program components and carefully evaluating PIF spillovers are critical to determining cost effectiveness.

Participating households

Total: 2,369

Experimental groups

FT group: Goat transfer, values-based and technical training

VT&TT group: Values-based and technical training only

G&TT group: Goats and technical training only

Control group: No programming

Funding (USAID)

$897,878

Project partners

Heifer International and IDA Associates

Impacts Summary

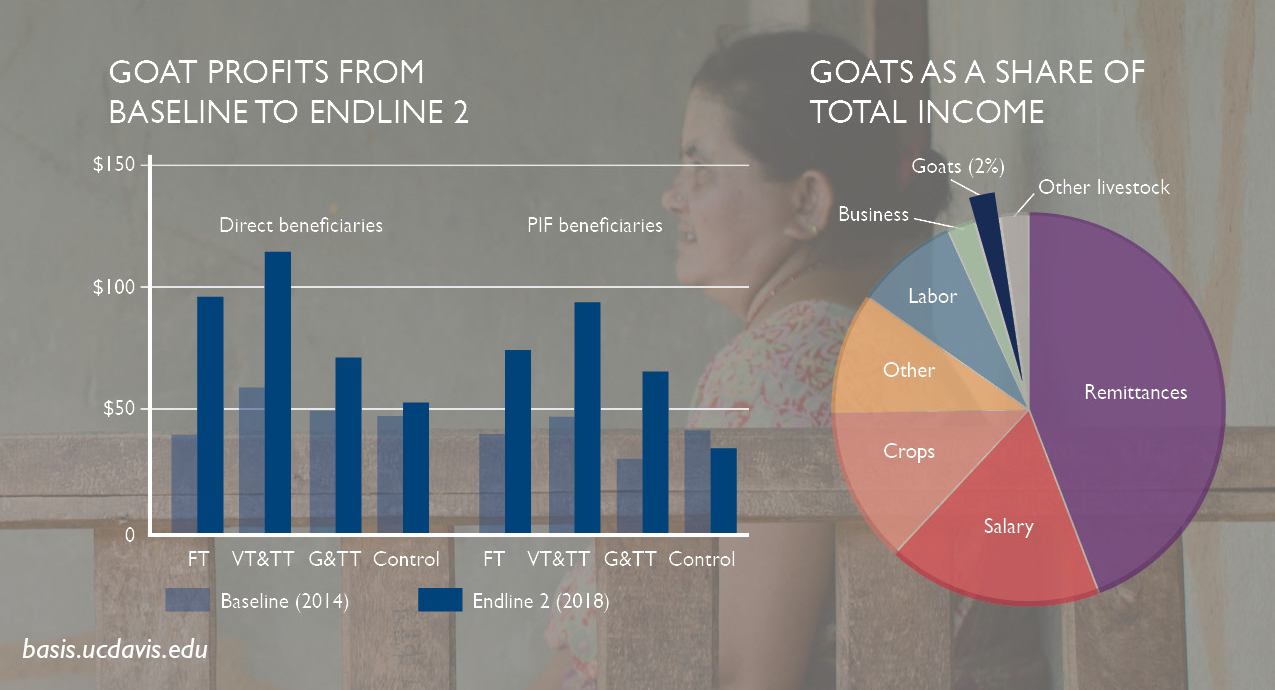

The program in Nepal had an impact on many outcomes directly related to goat-rearing as a livelihood. Compared to women in the control group, direct and PIF beneficiaries had bigger goat herds, improved livestock practices, more goat sales and higher profit from goat production. However, considering that goats contributed 2 percent of total household income, the impact on total household income was not detectable.

Direct beneficiaries were more empowered as a result of the SLVC approach, particularly in decisions related to goat enterprises. They also showed greater financial inclusion in all three treatment groups by the end of the program, but only women who received the values-based training sustained those impacts one year later. Impacts on financial inclusion were largely driven by savings group membership and whether a member personally had any savings.

The PIF mechanism that was central to the values-based training was fundamental in quickly scaling up the reach and total cost-effectiveness of the SLVC approach. The encouragement to pay-it-forward effectively extended the program’s reach to three out of every four women in communities where the program took place.

The PIF mechanism is clearly critical for achieving cost-effectiveness. Including both direct and PIF beneficiaries, the benefit-cost ratio for the FT group is 2.5. For the VT&TT treatment, which is substantially cheaper but achieves similar outcomes, the benefit-cost ratio it is 3.7. These BCRs overall are high, even under our conservative assumptions, in large part due to the program’s relatively low cost of about $130 per direct beneficiary.

Livestock Enterprise

The program directly affected goat production and related business. The SLVC approach was intended primarily as a means for women to quickly establish a productive asset and to share that benefit in their communities. In this regard, the program was a success. One year after the program concluded, goat-related revenues were nearly double.

By the end of the program, FT direct beneficiaries had 2.7 more goats on average than before the program started, and this increase persisted one year later. Interestingly, the increase in goat herd size exceeds the two goats each participant received individually. This increase also takes into account that FT direct beneficiaries gave away an average of 1.6 goats within a year after the program ended. In total, the original two goats more than doubled to an average 4.3 goats.

The training on animal care and husbandry contributed to these increases. Even women in the VT&TT group, who did not receive goats but did receive the technical training, increased the size of their herds by 1.4 goats. Women who received the full program were 51 percentage points more likely to have an improved pen, 37 percentage points more likely to remove manure at least weekly and 37 percentage points more likely to have a community animal health worker visit their home than women in the control group. Notably, these improved practices also increase the costs of production, and FT direct beneficiaries (those who received goats as well as values training) invested the most in their herds.

The values-based training appears to be important for increasing goat revenues. With the values-based training, annual gross goat revenue increased by $66 for direct beneficiaries after 3.5 years, double the increase compared to when the values-based-training was withheld.

The asset transfer increases program costs, but there is weak evidence to suggest it boosts the impact of the program. Counterintuitively, women who did not receive goats sold 70 percent more goats at the end of the program and 70 percent higher gross revenue. It is only after 3.5 years, one year after the end of the program, that FT beneficiaries catch up to VT&TT beneficiaries in terms of goat sales and revenue. It could be that the PIF mechanism, which requires re-gifting the received asset, delays the benefits for direct beneficiaries.

While the program did generate increases in livestock revenue and income, the amounts were not large enough to have discernible effects on total household income. Average goat revenue in the total sample was approximately $62, or 2 percent of household income. In the current market environment of the study area, the ceiling on income generation from goat production appears to be low. Heifer International is moving its focus to addressing local market structures by organizing self-help groups into goat producing cooperatives, which may give beneficiaries better access to urban markets and more negotiating power to get better prices.

Empower Women

An important question posed by this study was whether the program increased women’s empowerment, which can transform families and communities. Research has shown that when women serve a prominent role in food production, acquisition and preparation, empowering women can improve agricultural production, food security and children’s nutrition.[1] Women’s empowerment can also lead to better educational outcomes for children, particularly girls, leading to a more productive workforce and further increases in women’s empowerment.[2]

We found that the SLVC approach had a positive impact on women’s empowerment over goat production, and that these impacts persisted one year after the program’s end. Compared to women who did not participate in the program, direct beneficiaries of the full treatment were:

- 23 percentage points more likely to say they were owners or joint owners of the household goats

- 22 percentage points more likely to have control over decisions regarding the care and maintenance of goats

- 24 percentage points more likely have control over decisions regarding livestock sales

- 14 percentage points more likely to control the income earned from livestock.

To examine women’s empowerment over domains not directly related to goats we constructed an index that incorporated indicators from the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) developed by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Oxford’s Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) and USAID’s Feed the Future. WEAI is a survey-based index designed to measure the empowerment, agency and inclusion of women in agriculture. For our evaluation of SLVC approach in Nepal we modified the WEAI survey based on the unique circumstances of the local context.

Using our summary index, we found positive impacts on overall empowerment at the end of the program for direct beneficiaries in all three treatment groups. Improvements were driven primarily by higher levels of group participation and leadership. Women in the FT group were 16 percentage points more likely to participate in a community-based group. Relative to women in the control group, women in the FT group were 50 percent more likely to hold leadership positions.

One year after the program’s end, the impacts were smaller when comparing women in the three treatment groups to women in the control group, but this does not imply that the effects on empowerment had dissipated. Rather, it appears that women in the control group caught up. Using the original WEAI definitions of “adequate empowerment” among women who did not participate in the program, greater than 95 percent were adequately empowered for four of the seven subindicators, leaving little room for impact using the indicators we have.

Paying It Forward

The values-based trainings we evaluated covered the Heifer International “Cornerstones,” which include encouragement to pay benefits forward by providing technical training and giving the first two female offspring of their received livestock to other poor individuals in their community.

Paying it forward is a well-known concept, made especially popular during the holiday season in developed countries with widely publicized examples of paying for a stranger’s coffee or leaving an unfathomably large tip at a restaurant. It is rare to see the concept incorporated into anti-poverty programs. To our knowledge, no study has evaluated the impact of a program with this type of PIF model.

The SLVC approach we evaluated in Nepal included an innovation to the basic Heifer International PIF model: each direct beneficiary self-help group was tasked with recruiting up to five PIF self-help groups in their community with the goal of full saturation and complete adoption of improved practices and technologies within a short time frame. Heifer International facilitated its values-based empowerment training for both direct and PIF beneficiaries, but all other paid-forward trainings were implemented by direct beneficiaries with minimal support.

In late 2015, a second generation of beneficiaries joined the program through this PIF mechanism. These PIF beneficiaries formed new groups and participated in various trainings. Our research design allowed us to test the effectiveness of this part of the program, which is central to Heifer International’s model worldwide.

We observe effective recruitment through the PIF mechanism. In the FT group, over 80 percent of individuals targeted as PIF beneficiaries joined a Heifer self-help group. This number falls to around 70 percent in the VT&TT treatment group and 40 percent in the G&TT treatment group. FT beneficiaries gave away an average of 1.6 goats one year after the program’s end, almost reaching the two-goat target.

Does the program achieve the same impacts on PIF beneficiaries as on direct beneficiaries? We observed positive welfare impacts not only among households who received livestock and training directly from the program, but also for those brought into the program through the PIF mechanism. Like direct beneficiaries, PIF beneficiaries have larger herds, demonstrate improved livestock practices, and report higher income—both gross and net—from goats. They also have greater financial inclusion and appear more empowered, especially over goat enterprises, by the end of the program (although these effects are not as strong one year after the program’s end). These results are corroborated by evidence of much weaker PIF impacts when encouragement to pay-it-forward through the values-based training was withheld.

The PIF mechanism was fundamental in quickly scaling up the reach of the SLVC approach. PIF allows the program to have widespread impacts with low additional costs. The majority of households that could have been brought into the program were, and they enjoyed similar benefits as those targeted directly. These results suggest the PIF mechanism could be an important and cost-effective tool for achieving a broader development impact.

Benefits and Costs

An important question for any anti-poverty program is whether it is cost-effective. A benefit-cost ratio (BCR) divides the total of a program’s costs by the total of benefits it generates, resulting in a single number representing the dollar-for-dollar return on investment. A BCR of greater than one indicates a higher return than the program’s cost.

For this analysis, Heifer International provided detailed cost data. Operations costs include livestock, vegetable garden inputs, equipment and supplies for goat shelter construction, training costs and financial support for community animal health workers. Administrative costs include technical services, personnel and office expenses. We counted benefits as the total value of additional goats by the end of data collection, the total value of goats sold since the start of the program, a stream of expected future benefits,* minus goat production costs.

Including both direct and PIF beneficiaries, the benefit-cost ratio for the full treatment is 2.5. For the VT&TT treatment, which is substantially cheaper but achieves similar outcomes, it is 3.7. The PIF mechanism is clearly critical for achieving cost-effectiveness. For the G&TT treatment, under which there is no PIF mechanism, the benefit-cost ratio is only 1.4.

These BCRs overall are high, even under our conservative assumptions, in large part due to the program’s relatively low cost of about $130 per direct beneficiary. However, even these high returns for each dollar spent are much smaller than alternatives such as sending a family to find paid work elsewhere, as remittances represent nearly half of household income in Nepal.

It is unclear if intensifying the program by providing more goats or complementary inputs to decrease the cost of goat production would offer as high of a return. The asset transfer increases program costs, but there is weak evidence to suggest it has a meaningful impact on beneficiaries. It may also be that additional market-level or behavioral constraints - beyond lacking access to productive assets and human, social and financial capital - are simultaneously working against women’s transitions into becoming a successful entrepreneurs

*We conservatively estimated that increases in goat net revenue would continue into the future at 2018 levels into perpetuity, and used a 10 percent discount rate to calculate all future benefits.

Earthquake in Nepal

The “Gorkha” earthquake of 2015 devastated much of the country less than a year after the evaluation of the SLVC approach began. Of the seven districts within the study area, two—Dhading and Nuwakot—suffered catastrophic damage, which halted research in those two districts.

Heifer International responded with immediate relief that included a revolving fund establishing interest-free loans of $150 to some beneficiaries. Unlike the RCT, the revolving fund was implemented without randomization. Using matching methods to account for potential selection bias, our analysis showed that Heifer International beneficiaries appear to have coped with the earthquake more effectively than non-beneficiaries in terms of their coping strategies, especially to address food insecurity. In addition, households eligible for revolving fund loans were less likely to acquire new, undesirable debt from informal sources.

Sarah Janzen is an assistant professor of economics at Kansas State University.

Nicholas Magnan is an associate professor of agricultural and applied economics at the University of Georgia.

Sudhindra Sharma is executive director of Interdisciplinary Analysts (IDA).

William Thompson is an economist at IDinsight.

[1] Malapit, H.J.L., et al. 2019. “Intrahousehold empowerment gaps in agriculture and children’s well-being in Bangladesh.” Development Policy Review.

[2] World Bank. 2011. World Development Report 2012: Gender equality and development. World Bank Publications.

[3] Banerjee, A., et al. 2015. “A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries.” Science.

This project was funded by USAID Associate Award No. AID-OAALA-15-00002. This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) cooperative agreement 7200AA19LE00004. The contents are the responsibility of the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Markets, Risk & Resilience and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.