One Change to Hybrid Seeds that Could Boost Maize Productivity in Western Kenya

In Sirandu village in western Kenya, down a dirt road where girls in white school uniforms walk in a loose line of twos and threes, Joshua Oyugi follows a path through his two-acre property where he farms beans, cassava, sweet potato, banana and—most importantly—maize.

“Drought really spoils our crops,” says Oyugi. “You know, it has been very dry. It has really spoiled my bananas. But when it rains, you can’t believe.”

The climate Oyugi describes is unique to a corner of western Kenya situated between 1,000 and 1,500m above sea level. The challenge for maize farmers at this altitude is how to increase their yields when few, if any, improved maize varieties at local dealers are tailored for the local weather and ecological conditions.

From 2013-2015, a Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Assets and Market Access (AMA Innovation Lab) research team tested whether hybrid maize seeds tailored for Kenya’s mid-altitude regions could increase both yields and income for small-scale farmers like Oyugi.

It is early in February of 2017, two years after participating in the study, and the small plot Oyugi has set aside for maize has recently been tilled by hand with hired help from a neighbor. No one in the village owns heavy farming equipment. Oyugi was one of the farmers who decided to try the hybrid maize variety the study made available from Western Seed Company.

“It is better because of the yields,” says Oyugi. “And also the quality of that flour. It’s very good. People like it. The flour is sweet and white. Milk white, very white.”

Maize in Kenya

In Kenya, maize is everything. For about 96 percent of Kenyans it’s a major source of carbohydrates and provides more than a third of their daily calories. Most commonly, maize is ground into maize flour called unga and used to make ugali by adding it to boiling water and stirring until the mixture stiffens into a moist dough. On a plate with chicken stew or fried tilapia, ugali is most often a rounded, white loaf. For some Kenyans, ugali is the main meal.

Right now, Kenya faces a serious maize shortage due in part to drought and in part to government policies. The price of unga has spiked. In May of 2017, the Government of Kenya imported 30,000 metric tons of maize flour from Mexico. On July 4, Kenya signed a bilateral trade agreement with Zambia to import 100,000 metric tons of maize.

Beyond the impact of Kenya’s historic and continuing drought or government policies that have exacerbated shortages, maize productivity has been in decline for decades. Over three-fourths of all maize crops in Kenya are grown by small-scale farmers primarily for their own consumption.

For these farmers, maize yields at an average 1.6 tons per hectare of land are about a fourth of what’s possible with today’s technologies. Increasing productivity could make a particular difference across western Kenya where the average poverty rate is about 31 percent.

“Increased agricultural productivity is key to both increasing food security and reducing poverty,” says Mary Mathenge, director of the Tegemeo Institute for Agricultural Policy and Development and a principal investigator on the AMA Innovation Lab study.

The Promise of Hybrid Seed

Hybrid seeds are the product of breeding two distinct varieties of a plant into a single, first-generation hybrid strain that has all the desired characteristics of both parent lines, such as drought tolerance or resistance to disease. The new hybrid seeds also benefit from heterosis, also called hybrid vigor, which results in bigger plants and significantly higher yields.

For these reasons, hybrid seeds hold tremendous promise for small-scale farmers, especially those who are at risk of poverty and food insecurity. However, low adoption rates are common across developing economies worldwide, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Hybrid maize adoption rates in western Kenya, where the AMA Innovation Lab study took place hover around 40 percent.

One of the primary causes could be the ongoing costs of using hybrid seeds. While local varieties can be saved from ever harvest for planting in the next season, hybrids must be purchased each year. Saved hybrid seeds also yield plants that express at random the characteristics of their individual parent lines with little to no uniformity. They also don’t produce higher yields.

Another reason could be that the hybrid seeds available in western Kenya do not produce the promised yields. The hybrid maize varieties that have dominated Kenya’s maize sector since hybrids were first introduced in 1964 were not produced with the conditions of western Kenya’s mid-altitude areas in mind.

A Legacy of Large-scale Farming in Kenya

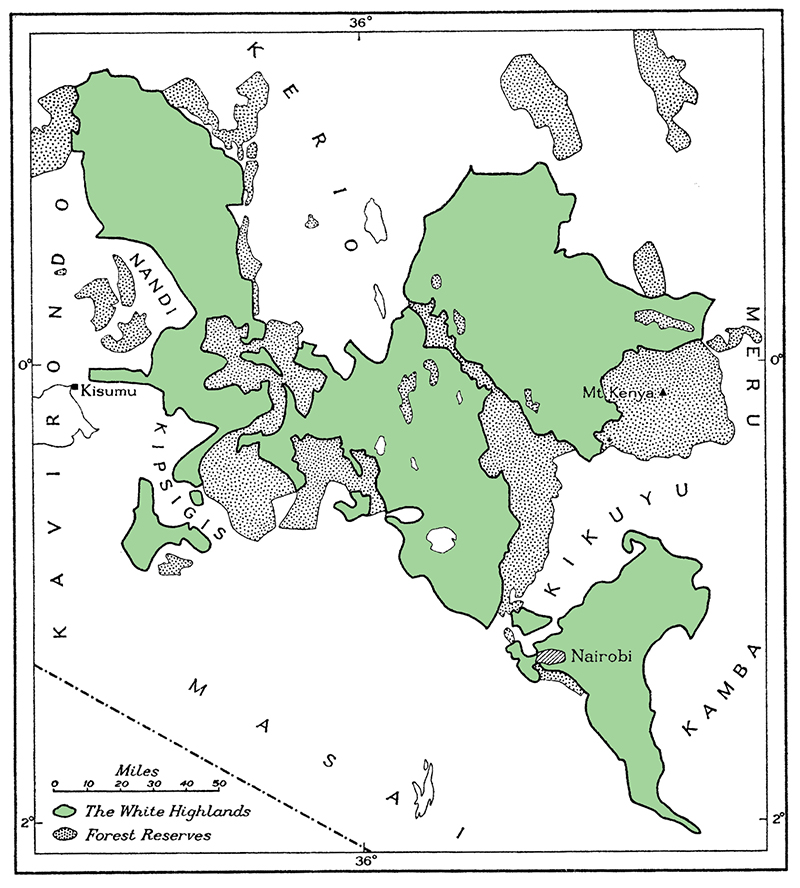

Kenya Seed is the largest seed company in Kenya. It was established in 1956 by the British colonial government to produce pasture seed for European settlers who managed large-scale farms across the Rift Valley and central Kenya. The “White Highlands,” as the area was called, was established at the turn of the 20th century with land grants for European settlers. Most of these farms were situated above 2,000m above sea level.

Kenya Seed’s 614 maize hybrid, first developed in 1986 for conditions in the White Highlands, remains one of its most popular hybrid varieties. However, environmental conditions at mid-altitude, where the climate is warmer and the growing season is shorter, make 614 less productive.

“It takes a longer period to mature,” says Tim Njagi, a Tegemeo research associate who worked on the AMA Innovation Lab study, “and if you’re planting it in a place where you use less fertilizer you are not going to see a bump in production.”

Kenya achieved independence from Britain in 1963 and steadily introduced a range of agricultural reforms. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, this included relaxing controls on the maize market and seed sector, effectively opening the market to competition. By 2010, over 78 seed companies were officially registered in Kenya.

Bringing Technology to the Farmer

Outside of Kisumu, not far from Lake Victoria, the highway passes through village towns where residents walk on the red-dirt shoulders past cows foraging in the grass. Cars and motorcycles, called piki pikis in this part of Kenya, all roll slowly over speed bumps made of dirt and sharp rocks. On stretches where the pavement ends, everyone moves at a crawl through orange dirt pitted deeply where rivulets of rain had at some point carried it away.

Saleem Esmail, CEO of Western Seed Company, was born near Kisumu. About 30 years ago he was a maize miller, then in 1986 he incorporated Western Seed Company, at first to sell traditional seed varieties or those developed by the national breeding program. When Kenya liberalized its seed sector in 1996, Esmail began to develop his company’s first hybrid maize variety. He submitted it for national performance trials in 1998.

“Small scale farmers in western Kenya who had adopted cultivation of maize in the early sixties were facing increasing challenges in yields,” says Esmail. “I believed I could bring a solution through improved technology adoption.”

Western Seed’s maize varieties quickly garnered attention by out-yielding Kenya Seed varieties by about 30 percent, especially in mid-altitude regions between 1,000 and 1,500m above sea level. This success attracted venture capital funding from AGRA and social impact investors that include the New York-based Acumen Fund. Acumen sparked the helped to fund the study by the AMA Innovation Lab research team from UC Davis and Tegemeo.

“You’ve got to generate the genetics in your breeding program that addresses all the constraints that the farmers have,” says Esmail.

Higher Maize Yields in Western Kenya

Between 2013 and 2015, about 1,200 farmers in Kenya’s former Western and Nyanza provinces took part in the AMA Innovation Lab randomized controlled trial (RCT). Farmers in the treatment group received Western Seed 250-gram trial seed packets and the option to purchase full bags to be delivered to their homes. The cost of the seeds was about KSH 2,000 per acre, which is about USD $20.

“We found that making those seeds available had a very large impact on maize productivity,” says AMA Innovation Lab director Michael Carter, the lead principal investigator on the study. “So there really was something in those seeds that was different.”

Grace Otieno’s farm is in Ndira, north of Lake Victoria and just south of the county seat of Siaya. She has young children, and manages the farm alone since the passing of her husband. Like most other small-scale farmers, she relies on rain to grow her crops.

“In case there is enough rain, I know how to do spacing and timing, so the moment the rain comes if I have somewhere to plant I can just wait,” she says.

Otieno bought Western Seed hybrids after receiving a trial packet. The following season she didn’t use hybrid seeds because she didn’t have the money to buy them. She used local seeds instead.

“The time I used Western Seed at least I got one and a half sack,” she says. “When I used the others I did get less.”

Across the sample of farmers higher yields were common. Average yields for farmers who had the option to purchase the hybrid seeds were about 40 percent higher compared to farmers in the control group. For farmers like Oyugi in Sirandu, who already consistently used hybrid seed, that increase was 80 to 90 percent.

Incomes also went up, but modestly. Across the sample, maize only accounted for about 13 percent of total household income in the mid-altitude zones on average.

A Place for Hybrid Maize in Kenya’s Future

The Sarova Panafric Hotel in Nairobi is perched on a hillside above Kenyatta Avenue, a busy street in the center of a city housing over 3.5 million people. In the early morning cars and buses clog the lanes and the sidewalks fill with men and women who can walk to work, avoiding hours stuck in traffic like those who leave home as early as five a.m.

It is here at the Sarova Panafric on February 8, 2017 that the AMA Innovation Lab research team presented their findings to an audience of over 60 Kenya government officials, seed sector representatives, development professionals, journalists, researchers and a handful of farmers who participated in the study.

Mary Karanja, representing principle secretary of the State Department of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries Richard Lesiyampe, offers a message for the event. Kenya needs further research to develop acceptable maize varieties, to test the efficacy and efficiency of common pesticides and to identify the best cereal, legumes and crops that maximize land use.

“Without farmers’ determination and ceaseless efforts we would not feed this country,” she says.

Joseph Saka is a maize farmer from the town of Homa Bay in western Kenya. He participated in the study, and at the conference sits at a middle table wearing a long black coat and a lightweight buttoned shirt until he is asked to stand behind the podium to speak about his own experience.

“It’s difficult to produce a new idea to a group of people in a local area,” he says, “but after some time, several of us had good experiences.”

At the conference, the consensus is that increasing maize productivity nationwide depends in large part on increasing productivity among small-scale farmers like Saka. The Western Seed experiment showed that hybrid seeds tailored for agro-ecological niches can help. However, there remain other complex challenges that go beyond developing the seeds.

One of these is ensuring that authentic, high-quality seeds and fertilizer are available at local agrodealers. As a research assistant on the AMA Innovation Lab study, Emilia Tjernström, now an assistant professor of public affairs and agricultural & applied economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, tested seeds and fertilizers purchased from local shops.

She found that for seeds the packaging varied in appearance and condition, as did their price and color. Importantly, the average germination rate was 76 percent. In some samples, as few as zero seeds germinated. Kenya’s seed regulations stipulate that even for basic seed, 90 percent should not be damaged or poor-sprouting. Fertilizers provided by the research team out-yielded local-bought fertilizers by up to 100 percent.

Another challenge is how well the for-profit seed sector can reach historically underserved farmers. Tailoring hybrid seeds for such a niche may not be financially sustainable even for a small company like Western Seed, even with a market of ready buyers.

“If agroecological niches are not profitable,” said Carter, “then what’s the public policy to get the genetic material there?”

Media contact:

Alex Russell, (530) 752-4798, parussell@ucdavis.edu