Health insurance is one of the most important policy issues in the developing world today. Developing countries suffer 90% of the global disease burden but represent only 12% of the world’s spending on health care. More than half of health expenditures in poor countries are out-of-pocket payments by individual households.

This situation is particularly dangerous for the rural poor. Agricultural activities can lead to high instances of injury and illness. Health shocks and associated high medical costs can cause poor families to sell productive assets or reduce consumption to the point where economic well being is endangered and the family’s health and the children’s educational opportunities are compromised. These strategies for coping with health issues can trap families in long-term poverty.

Health insurance may improve health and economic outcomes among the poor. Past research has revealed the large impacts that health insurance and changes in the price of health care have on health and well being. Most studies find that the effects are largest among the poorest people, whether in a developed or developing country context. Insurance may increase a family’s economic well being by allowing it to preserve its assets and reduce the need for child labor to cover medical expenses. Insurance can stabilize consumption by decreasing the amount of spending on health care. Also, good health increases labor supply and productivity, so to the extent that insurance provides access to good quality health care, the family can achieve higher productivity.

Health insurance may improve health and economic outcomes among the poor. Past research has revealed the large impacts that health insurance and changes in the price of health care have on health and well being. Most studies find that the effects are largest among the poorest people, whether in a developed or developing country context. Insurance may increase a family’s economic well being by allowing it to preserve its assets and reduce the need for child labor to cover medical expenses. Insurance can stabilize consumption by decreasing the amount of spending on health care. Also, good health increases labor supply and productivity, so to the extent that insurance provides access to good quality health care, the family can achieve higher productivity.

Despite the vulnerability of the poor to illness and injury, and the drastic consequences that can result, health insurance in developing countries remains rare. It can be difficult to design health insurance programs that effectively reach the target populations. At the same time, insurance providers may not find it financially sustainable if people with the highest risks and costs are the ones that are more likely to buy insurance.

Micro-health insurance is a promising product to help the poor with health care. Policymakers and aid agencies can benefit from a rigorous analysis of the ability of micro-health insurance to reach the poor and provide access to care that can help protect or even promote economic wellbeing. In addition, such an analysis can help insurance providers understand whether people with high average medical costs are heavy purchasers of health insurance. Our project will evaluate the effectiveness of an innovative rural health insurance program in Cambodia, which offers one of the few health care insurance options to the poor and seeks to enable families to cover health care costs without risking a cycle of impoverishment.

In 1998, a French NGO launched a health insurance program called SKY (“Sokapheap Krousat Yeugn,” which in Khmer means “Health for Our Families”). Currently, SKY is funded by donors but the plan is for it to become financially self-sustainable. SKY’s goal is to provide protection from catastrophic health expenses, while at the same time encouraging the use of public health facilities that meet minimum quality standards.

SKY also hopes to increase the quality of care at public facilities by providing them with a steady and predictable income stream. The SKY program is directly targeted at increasing access to health care by eliminating the per-visit cost of visiting public facilities, encouraging the use of only highquality public facilities, and encouraging women to give birth at health care centers. By encouraging early treatment at qualified facilities, SKY has the potential to increase health-seeking behaviors and improve health outcomes.

SKY offers insurance to households at a rate ranging from $0.50 per household per month for a single-person household to $1.83 per household per month for a household with eight or more members. Households must purchase insurance for a minimum of six months. To join SKY, households pay their first month’s insurance premium plus two additional months in advance, to be held as reserve in case of underpayment. To encourage initial take-up, households offered insurance for the first time are offered lower premiums for the first six-month period.

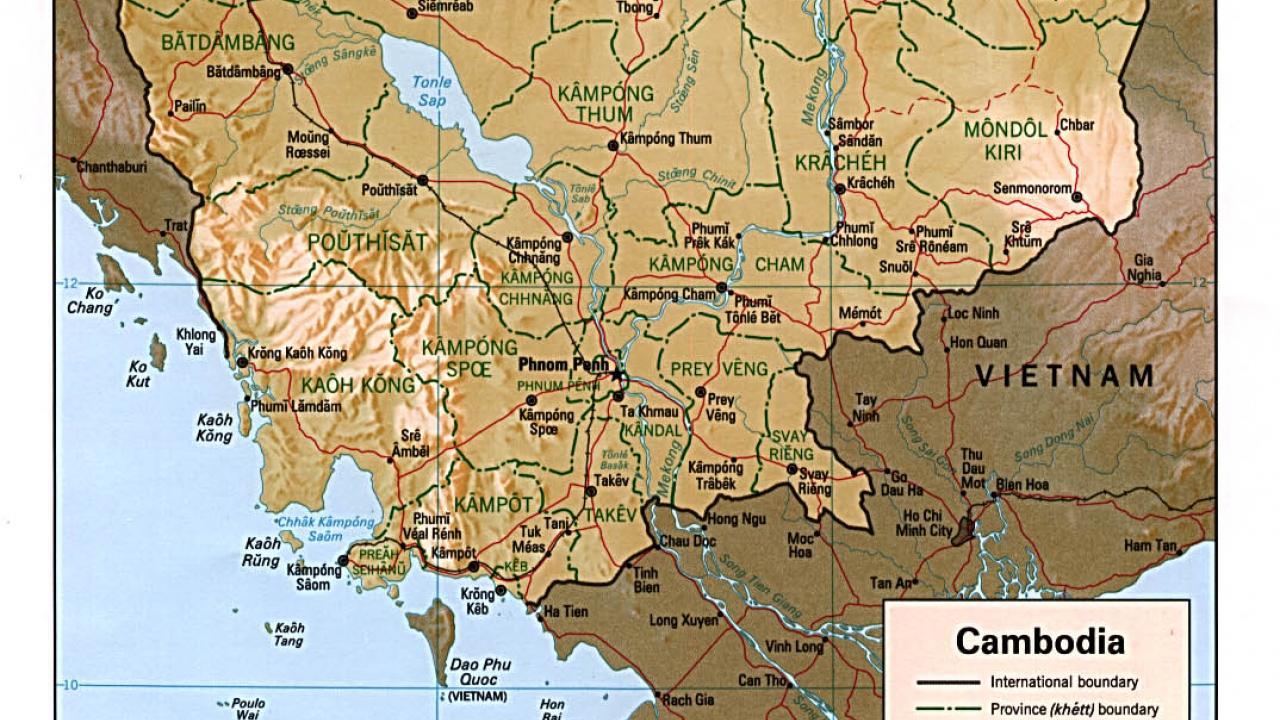

Currently, SKY offers insurance to households in several rural districts in Takeo and Kandal provinces and recently expanded into the capital, Phnom Penh, targeting specific groups such as garment workers and market vendors. In December 2005 the program had 4,392 beneficiaries from 917 households, which was a 160% increase from the previous year. Take-up of insurance ranges from 2% in regions where insurance was only recently introduced, to 12% in the longest-served regions. SKY plans to expand to additional districts in Takeo province, which has a population of 870,000 and a total of 70 health centers and five hospitals.

Cambodia is among the world’s poorest and unhealthiest nations. Health shocks are a major factor in loss of land and can push households into deeper poverty when high-quality and affordable health care is not available. Poor quality of care, long distances to health facilities, and prohibitive expenses have led to a situation where fewer than 60% of the poor in need of health care actually use it. Lessons learned from an evaluation of the SKY program can help determine whether micro-health insurance is offered more widely to the people of Cambodia.

Testing SKY

Despite the potential for great benefits from a program such as SKY, very little is known about the ability of micro-insurance programs to improve health and economic outcomes. We will evaluate the effectiveness of SKY using a randomized controlled trial that will help us analyze several important questions:

- Is “adverse selection” (where those with high costs are more likely to buy insurance) an obstacle to a financially sustainable private health insurance market?

- What insurance prices and contracts minimize adverse selection, promote financial sustainability, and improve outcomes for the poor? • Is health insurance a good way to increase health outcomes?

- Is health insurance a good way to decrease the vulnerability of poor populations?

The central methodological tool of our evaluation is the use of randomization of insurance premium levels to vary treatment conditions among households within a village. A pre-intervention baseline survey of approximately 3,000 households with over 12,000 individuals and follow-up surveys of the same households will be conducted over the four-year experimental period. The surveys will cover the multiple areas that the health insurance program attempts to influence: health, asset vulnerability, investment and saving decisions, and risk management. We will examine how baseline characteristics affect purchase of insurance and examine how health insurance affects these outcomes.

Before SKY offers its health insurance products in a village that previously has not had access to the insurance, we will conduct a baseline survey of a random sample of people in the village. The survey will include health, health behaviors, past health care utilization, past spending on health care, risk behaviors and attitudes. We also will collect information on general economic and demographic characteristics of the household.

We then will work with SKY to randomize the offer of insurance to potential participants. When introducing its program in a village, SKY holds a meeting to outline the program to village members. Under our controlled experiment, SKY will use a drawing to randomly offer the meeting participants coupons redeemable for insurance. Of the households at the village meeting, 35% will receive a coupon for five months of free insurance, while the remaining households will be entitled to a one month discount on insurance, which is the usual policy for the SKY program.

The randomization of coupon offers enables us to do three things. First, it allows us to eliminate the effect of selection in our analysis of the impacts of health care. Second, it allows us to measure selection by comparing characteristics of the insured to the uninsured, and by comparing the characteristics and utilization of those who chose to buy insurance at different prices. Finally, it allows us to sketch out a demand curve for insurance, as we will know the rate of take-up at different price levels.

Following the meeting, a portion of the households that attended the village meeting (and were not already given the survey) will be administered the baseline survey. Using data gathered, we will be able to answer questions on what household characteristics induce families to buy insurance, shedding light on competing theories of selection. We also can compare the characteristics of households willing to buy insurance at different prices. We hypothesize that households that are willing to buy insurance at higher costs (without coupons) would be more adversely selected (that is, they will have greater health needs). We also hypothesize that those who buy insurance may have fewer alternative ways to mitigate risk.

Just over a year later, we will carry out follow-up surveys of all households originally interviewed. The follow-up survey will contain questions concerning the experience with the SKY program for those who purchased insurance. This survey will give us information on how SKY changes utilization behavior, and will measure economic impacts of SKY such as changes in out-of-pocket expenditures. A second follow up a year later will repeat most of the same topics, emphasizing changes in health outcomes and catastrophic expenditures as a result of SKY membership.

We will complement the statistical analysis with a qualitative evaluation of the SKY program, involving interviews and focus groups with the donor and SKY personnel, insurance agents, customers, health care providers, and those who declined to purchase health insurance. The analysis will examine impacts SKY has on the health system, including public health facility revenue, changes in supply of drugs and medical equipment, and changes in health worker income and work patterns. The analysis also will look for unanticipated effects of the program.

Our first goal is to measure how effectively health insurance protects the poor from the risks associated with high medical costs, loss of income, and reductions in investments and productive assets. Rigorously documenting the impacts of this program—both what works and what does not—will allow ministries of health, donors and policymakers to learn lessons from the innovative program.

The initial investment in health insurance for the needy in Cambodia can multiply to improve health insurance, and, more broadly, health and economic outcomes, in developing countries around the world. The evaluation also will allow us to measure how insurance affects health utilization behavior, and whether this increased utilization in turn leads to positive health outcomes.

Our second goal is to discover who purchases insurance at different premium levels: those with high expected costs, those who are most cautious, or a combination. This information is crucial, for questions remain about how financially sustainable insurance can be, especially when private insurance is subject to adverse selection.

If adverse selection is severe, risks will not be pooled and premium levels will not be able to cover the high costs of care. By studying the profiles of users of health insurance, we can measure the extent of adverse selection and better understand how the poor deal with risk both with and without insurance, and how insurance can help to mitigate the vulnerability of the poor. Such measurements should inform policy making towards health care globally.

As an additional aspect of our evaluation, we will be able to measure impacts of health insurance on various demographic groups. Understanding how family composition affects take-up of insurance, and how insurance affects outcomes for different demographic groups (specifically women, children, and the elderly) will be an important outcome of the evaluation.

We will use the results to examine how health insurance affects health and economic outcomes and how adverse selection and premium levels affect the financial sustainability of micro-health insurance. We will apply these lessons to analyze the optimal insurance contracts that provide maximal insurance to the poor while minimizing costs. We will then analyze the trade-offs between the value of insurance to the poor and the financial sustainability of the insurance providers. Those lessons will help us design the optimal business model for a micro-health insurer.

Local and Global Policy Impact

Improved quality of care and improved access to care can lead to better health outcomes. In turn, better health can result in positive economic outcomes for families. By covering medical costs in the event of a catastrophic health shock, a successful micro-health insurance plan can prevent people from selling off productive assets, depleting savings, and reducing investments in children’s health and education to pay medical bills. By ensuring that medical bills can be paid, micro-health insurance can help free up resources so that households can make additional investments, contributing to asset accumulation.

The evaluation of SKY’s health insurance program coincides with USAID’s global goals of promoting health and with its objectives in Cambodia of increasing the use of health services. The evaluation also supports the goals of the Cambodian government, as the SKY program has become a model that the Ministry of Health hopes to learn from in expanding Cambodia’s health insurance system.

The evaluation of SKY’s innovative insurance product will serve as a global public good. Developing countries have been looking for ways to protect their most vulnerable populations from the negative consequences of health shocks. In addition to Cambodia, various countries in the region, including the Philippines, Laos, China and Vietnam, have been experimenting with health care insurance, both community-based and government-run. As health insurance is a new product in this region, the results of this evaluation can be used to by other governments and aid organizations to determine if voluntary health insurance is an effective way to meet some of the health goals of the developing world, and if future projects of the sort should be funded.

By rigorously documenting the impacts of the SKY program—both what works and what does not—we can provide information to health ministries, donors and policymakers around the globe. Thus the initial investment in health insurance for the needy in Cambodia can multiply to improve health insurance, and, more broadly, health and economic outcomes, in developing countries around the world.

Related Reading

Currie, J. and J. Gruber. 1996. “Health Insurance Eligibility, Utilization of Medical Care, and Child Health.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111(2): 431-66.

Gottret, P. and G. Schieber. 2006. Health Financing Revisited: A Practitioner’s Guide. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

Kenjiro, Y. 2005. “Why Illness Causes More Serious Economic Damage than Crop Failure in Rural Cambodia.” Development and Change 36(4): 759-83.

Manning, W.G., J.P. Newhouse, N. Duan, E.B. Keeler, and A. Leibowitz. 1987. “Health Insurance and the Demand for Medical Care: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment.” The American Economic Review 77(3): 251-77.

SKY website. 2006.

Wagstaff, A. and M. Pradhan. 2005. “Health Insurance Impacts on Health and Nonmedical Consumption in a Developing Country.”

World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3563. World Health Organization. 2007. Cambodia Health Situation.

Publication made possible by support in part from the US Agency for International Development Cooperative Agreement No. EDH-A-00-06-0003-00 through the Assets and Market Access CRSP. All views, interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting or cooperating organizations.