In the pursuit of financial technologies to help farmers effectively manage risk, index insurance has shown promise by avoiding the high costs of verifying individual losses. Instead, a payout is triggered when a threshold level on an index is reached, usually measured remotely. Early index insurance products insured farmers against poor weather outcomes; now, some contracts cover all perils of production—with area yield as the index—in response to the multiple types of hazards facing farmers.

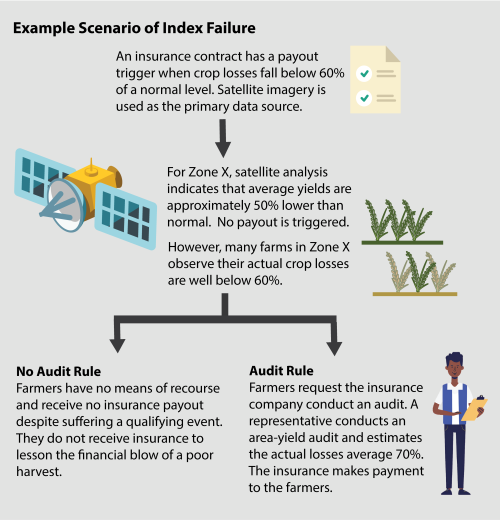

Still, some characteristics of index insurance contracts limit their protection of farmers. ‘Basis risk’ describes the possibility that farmers experience a loss that should be covered but is not picked up by the index, so farmers are not paid. Such occurrences worsen the economic well-being of insured households, who spent money on a premium and then suffer an uncovered loss, and undermine trust in insurance as a reliable risk management tool.

A fail-safe mechanism to protect farmers against basis risk may be an important addition to some insurance contracts, ensuring they do no harm. Specifically, an audit rule that is activated when farmers believe the index has failed can give farmers increased confidence that their insurance will protect them as intended.

Limitations of Remote Estimates

MRR has found that estimation of vegetation levels through analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery offers the most accurate estimate of yields. The satellite technology is increasingly powerful, offering precise imagery that supports accurate detection of losses most of the time. However, even as satellite technology and analysis methods improve, the resulting estimates of vegetation levels do not always capture the full picture of crop growth. That is, indices based on the most accurate estimation methods can still fail.

Favor Can Be Fickle

In some cases of index failure, when farmers experience substantial losses but the index does not trigger, an insurance provider or supporting NGO decides to make a payout. This is known as an ex-gratia payment, meaning “by favor,” as the contract does not require it. This approach still places farmers in a position of uncertainty, unable to rely on the insurance to protect them, as they do not know if the provider will make another ex-gratia payment the next time the index fails.

A Fail-Safe Audit Rule

To ensure that index insurance products protect farmers as intended, MRR recommends that contracts include an audit rule. This fail-safe mechanism offers a back-up in case of an index measurement failure. With an audit rule, the insurance contract stipulates that if farmers notify the insurance provider that they experienced losses at a quantity covered by their contract, but the index was not triggered, the provider will conduct an on-the-ground audit of the respective geographic zone.

Under the audit, an agronomist measures samples of mature crops from local farms and determines the area average yield—a method known as crop-cutting. If the audit confirms that the area yield losses exceed the insurance contract threshold, the insurance company issues the payout to all covered farmers in the zone.

Audit Rule Considerations

The audit provision can specify a minimum proportion of farmers who must register an index failure complaint in a specific zone in order to trigger an audit. It is essential that farmers are aware of their right to submit an index failure complaint, without fear of negative consequence, and have an easy way to do so. Depending on the context, extension agents might also be engaged to report index failures.

As insurance providers adopt an audit rule, it is essential that they plan for increased costs as they determine the plan’s premium. Though the rule might not bring additional costs in a given year, over time additional payouts and audits will add to costs, meaning the provider may need to increase the premium.1

A marginally higher premium will not necessarily translate into decreased uptake. When testing aversion to insurance ambiguity in Mali, MRR researchers found that farmers were willing to pay more for a hypothetical insurance contract without the uncertainty of basis risk.2

The audit rule does not reduce the importance of making the index as accurate as possible, as frequent audits would create significant expense, undercutting the savings of index-based insurance.

In order for index insurance to realize its intended development impacts, it must reliably provide payment for covered losses. An audit rule can be an effective fail-safe provision for some insurance contracts to safeguard farmer welfare. The audit rule is complementary to commercial objectives, as more reliable insurance contracts are expected to increase demand.

- 1

In Mozambique and Tanzania, MRR researchers estimated additional payouts that would accompany an audit rule. The insurance companies rolled the estimated additional cost into the premium for the contract. Boucher, S.R., Carter, M.R., Flatnes, J.E., Lybbert, T.J., Malacarne, J.G., Mareyna, P.P., Paul, L.A. 2024. “Bundling Genetic and Financial Technologies for More Resilient and Productive Small-Scale Farmers in Africa.” The Economic Journal, 134 (662): 2321-2350.

- 2

Elabed, G. and Carter, M., 2015. “Compound-risk aversion, ambiguity and the willingness to pay for microinsurance.” Journal of Economic Organization and Behavior, 118: 150-166.