Measuring Sustained Impacts of Agricultural Interventions

When a development intervention ends, what happens? Are results sustained? What about after a shock? Would results have been deeper or more durable had the program run for longer?

Though such questions are critical for policymakers in effectively pursuing their goals, they often go unanswered.

Recently, two studies supported by the MRR Innovation Lab have measured the impact of agricultural interventions after their end. One, in Bangladesh, is structured as a traditional ex-post evaluation that measures the impact of a program that was designed with a randomly selected treatment group. The other, in Uganda, takes a novel approach in measuring the effect of program end on randomly selected groups that are phased out of activities. Together, these two studies show very different ways of approaching similar questions.

A Tale of Two Studies

Professor John Hoddinott, Cornell University and a team at IFPRI took a traditional, comprehensive Random Controlled Trial (RCT) approach to assess the impact of the 2015-2018 Agriculture Nutrition and Gender Linkages (ANGeL) project in Bangladesh. Implemented by government agricultural extension agents, the trainings-based intervention was designed to promote agricultural diversity, increase farm household income, improve nutrition and empower women. The RCT endline survey found that ANGeL households improved their agricultural production practices, their children’s diets and relationships in the home. Four years after the project end, the team went to find out what impacts had been sustained – particularly following the dual shocks of Cyclone Fani and the economic lockdowns of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Professor Stephen Smith, George Washington University and a team of researchers also wanted to measure what program impacts were sustained following activity end—or, in their words, “survive program termination”—but took a different tack. BRAC’s program to improve crop yields of smallholder women farmers in Uganda, via improved seeds and cultivation methods, was not experimentally implemented. Smith and his team used a randomized phaseout of the program activities to draw comparisons between those still participating in the program and those who had participated in the program for four years and were now three years (six agricultural seasons) post-intervention. This method allowed them to draw unique conclusions about the impact of ending the program.

Traditional and Novel Counterfactuals

To ensure an evaluation actually measures impact of an intervention, a counterfactual – or, control – group is needed.

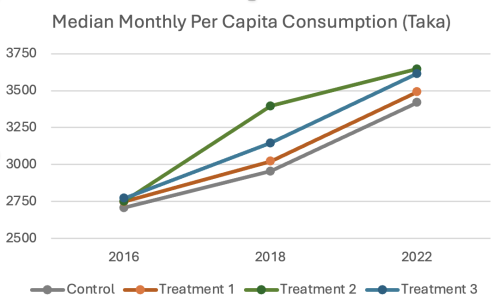

In the RCT, the control group was assigned at the beginning of the intervention. The ANGeL intervention never came to those communities. As surveys were conducted, change in variables like consumption were compared not to the initial levels, but rather to those of the control, to understand the impact of the intervention. While treatment groups experienced gains, increasing numbers among the control group indicated the difference attributable to the intervention. (Program participants experienced different levels of treatment between agricultural, nutrition and gender interventions – for more detailed information, see Evidence Insight.)

For BRAC, the counterfactual group is very different, and even counter-intuitive: it is the participants continuing to be treated with the intervention. This novel approach still employs randomization as the method for determining which sub-sample of program geographies would continue versus phase out activities. (Smith’s team also surveyed a never-treated group, using various techniques to confirm that the intervention itself did have an impact, and found positive program impact through an RCT of the program in a different part of the country. They note an original experimental design of the intervention would have enabled even stronger conclusions.)

Bangladesh: Sustained Impacts to Well-being

Hoddinott’s team is still analyzing data around behaviors. So far, their analysis has focused on higher-level measures of well-being: consumption, nutrition, assets, and resilience. Overall, they found that the ANGeL program tended to have the biggest impacts on those who participated in both the agriculture and nutrition interventions. Those participant groups continued to have higher well-being measures than the others four years on, despite the dual shocks of the hurricane and pandemic lockdowns. (Full paper here.)

Uganda: Sustained Uptake, Learning, and Markets

Smith’s team measured the differences in use of improved seed and cultivation behaviors between the formerly treated and continued treatment groups. They found that the program phaseout did not appear to lead to a decline in either. These results suggest that the initial learning and experience of the product and behavior, subsidized and encouraged under the program, was sufficient for farmers to experience continued benefit of higher yields, making them willing to continue the extra cost and effort. In other words, the intervention had served its purpose.

A closer look at the Uganda data around post-program supply and demand for seed paints a telling picture of a transition between a temporary, subsidized program and longer-term market system. When program-appointed sellers stopped receiving subsidized seeds, many of them discontinued their sales activities. However, rather than returning to unimproved seed, many of the former participants found other market actors who sold the improved seed—an extremely strong result for sustainability. This transition occurred gradually over the six seasons following the phaseout, underscoring the value of measuring several years after end of activities. (Full paper here.)

Looking Ahead

Studies with a counterfactual offer tremendous value in understanding the value of an intervention. The RCT remains the gold standard, while the randomized phaseout offers a novel new approach to test the value of continuing an intervention.

These studies, conducted 3-4 years after program end, both show sustained results. In Uganda, Smith’s team found sustained uptake of improved behavior and seed—even as the purchase of seed transitioned to the unsubsidized market. In Bangladesh, Hoddinott’s team found many of the program’s impacts had sustained among some treatment groups, even after dual shocks, but the gap between treatment and control groups was starting to narrow.

John Hoddinott offers this takeaway: “The ultimate test of the effectiveness of development interventions occurs after they are over. This research shows that, with careful design, it is possible to do so. Even better, these two studies show that interventions in the agriculture and nutrition space have sustained effects, even in the face of significant shocks.”