Making Index-based Insurance Fully Available for Women

This article originally appeared in the BRAC Institute of Governance & Development blog.

The BOMA Project’s Rural Entrepreneur Access Project (REAP), modeled on BRAC’s Targeting the Ultra-poor Program (TUP), builds the business assets and the economic empowerment of poor women in pastoralist communities in East Africa.

“The BOMA Project’s approach is a uniquely adapted model that tackles the challenges specifically suited to the context of the drylands of Africa,” said BOMA Vice President Jaya Tiwari, “especially for women and girls in highly patriarchal societies in pastoralist, rural Kenya.”

A midline evaluation of the REAP program revealed that women who were offered the REAP program increased their business assets by 324 percent relative to a group of otherwise identical control women. Additionally, their families’ cash earnings increased by 32 percent and their savings by 509 percent relative to the control group. Although these impacts are similar to those of other TUP-based “graduation programs,” the context is not.

Pastoralist households in Northern Kenya are particularly susceptible to climate change-induced droughts. These droughts can destroy over 50 percent of a household’s wealth in just a few months.[1] Pastoral women are particularly vulnerable to losing hard-won gains from these natural calamities. The assets and livelihoods that these women have so painstakingly constructed with the aid of graduation programs like REAP require protection.

Index-based livestock insurance (IBLT for index-based livestock takaful), which is based on satellite measures of forage availability, has been shown to protect families’ assets and consumption standards.[2] IBLT has been proven to be effective in protecting families’ assets and consumption standards. But one problem persists - mobile pastoralism is cast as a decidedly unambiguous male activity. It is men, not women, who travel across the open rangelands in search of forage for their livestock. While the women-owned shops seeded by REAP, which are predominantly small shops and training businesses in fixed locations, are not directly dependent on rangeland forage conditions. Indirect dependency, however, is another story - resources for the entire family are contingent upon livestock-generated income.[3]

When we first started working on finding an insurance solution to protect the business assets of women in pastoralist regions, we quickly found that women were well aware of and sensitive to their indirect exposure to rangeland risk. More importantly, women were acutely aware of their responsibility to not only protect their businesses, but also to feed and care for their families in moments of climate stress. We experienced an ‘ah-ha’ moment when we realized that framing insurance to speak to women’s indirect risks and responsibilities would not only be straightforward, but possibly more effective.

In collaboration with professor Andrew Hobbs of the University of San Francisco, we created a video game titled “SimPastoralist” to test our idea (check out a video and more details about the game here). The game simulates pastoralist life with an emphasis on decisions around livestock rearing and insurance. In each round pastoralists decide how many goats and how much insurance to buy. If the rains are good, goats reproduce and insurance does not pay out, but if the rains are bad, goats die and insurance payouts offset their losses. Playing SimPastoralist helps participants understand insurance and also gives us data on how people make insurance decisions. Since we wanted to study whether framing insurance around women’s indirect risks and responsibilities would increase demand, we explained the insurance in the traditional “protect-your-livestock” way in half of the sessions and in the other half emphasized the fact that insurance payouts could be used not just to protect livestock but also to buy food for the household or pay school fees in the event of a drought. Results from the experiment were striking—reformulating IBLT to speak specifically about women’s roles and responsibilities almost doubled the demand for insurance among women relative to the traditional “protect your livestock” framing.

Our insurance partner, Takaful Insurance Africa, also found the results striking. With the support of Takaful Insurance Africa, The BOMA Project, and WEE-DiFine, we applied our field findings to the insurance contracts that Takaful sells.[4] The result was IBLT for Families, which offers women the opportunity to purchase insurance in Family Units instead of tropical livestock units. The payout value of IBLT for Families was calculated based on the amount of money that Kenya’s emergency cash transfer program provides to families in moments of extreme need. This reframing of the insurance focuses the buyer´s attention on the number of family members they need to feed in the event of a drought emergency.

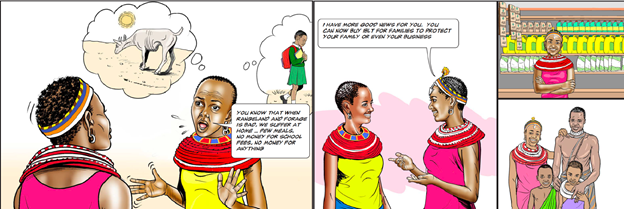

As shown in the cartoon panels below, women’s indirect exposure to forage risk was incorporated into the training material; so too was the ability of family units of coverage to protect women’s families and their newly accumulated business assets.

IBLT was sold during two sales periods: one in February 2021 and another one in September 2021. We conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in 50 study areas where the control group received conventional livestock framing (presented using similar training materials), and the treatment group received the novel IBLT for Families approach. The sales data during this period show that reintroducing IBLT for families with a special focus on women’s risks and responsibilities increased demand for insurance, relative to conventional framing.

While preliminary results are promising, final sales numbers will only be available in a few months time. Moreover, we are presently refining their initial analysis by incorporating additional information on prior insurance purchases. With more detailed information on living standards, attitudes, mental health, and women’s empowerment in hand, we are poised to dive deeply into an analysis of the impacts of making insurance fully available to women through efforts such as IBLT for Families.

[1] Janzen, S. and M.R. Carter (2019). “After the Drought: The Impact of Microinsurance on Consumption Smoothing and Asset Protection,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics.

[2] Chantarat, S., Mude, A. G., Barrett, C. B., & Carter, M. R. (2013). Designing index-based livestock insurance for managing asset risk in Northern Kenya. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 80, 205–237.

[3] Hobbs, Andrew (2020). “Insuring what matters most: Intrahousehold risk sharing and the benefits of insurance for women,” working paper, University of San Francisco.

[4] Jensen, N., Mude, A., Vrieling, A., Atzberger, C., Carter, M. R., Meroni, M., & Stoeffler, Q. (2019). “Does the design matter? Comparing satellite-based indices for insuring pastoralists against drought,” Ecological Economics, 162, 59–73.