A New Kind of Drought Insurance for Women in Kenya’s Arid Rangelands

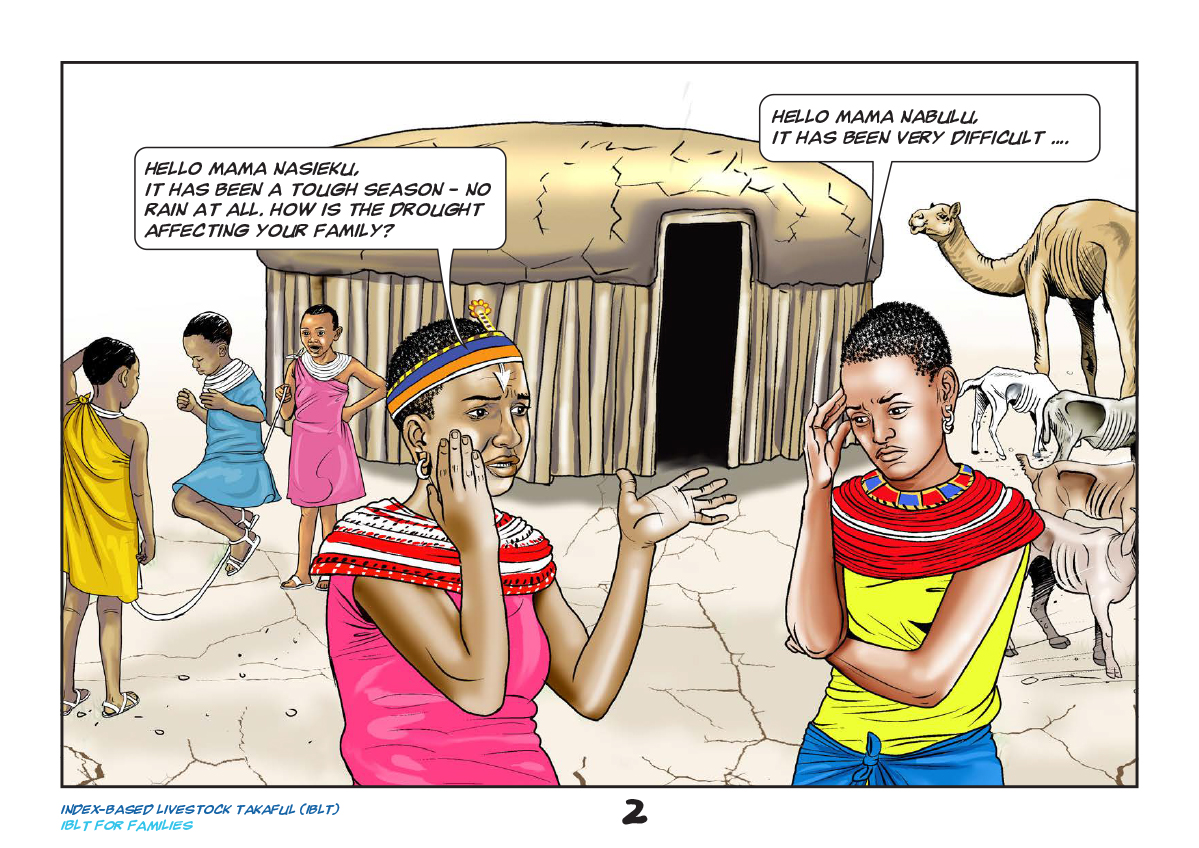

Mama Nabulu visited her friend Mama Nasieku after the wet season ended with no rain at all. When Mama Nasieku said that her family lost half their goats and cattle, Mama Nabulu asked if she’d heard about the insurance that helps in drought, a new kind that’s not just for livestock.

This story was told with a comic strip during a recent community meeting in Samburu, Kenya, a remote rural district where the climate is so dry that the only means for most people to make a living is with livestock. Women at this meeting were taking part in a program that provided them financing and training to start a small business. Now they were learning about “Family Insurance,” which could help them take care of their families during drought.

“Family Insurance completes the suite of support women need in this environment to build independent and resilient livelihoods,” said Michael Carter, MRR Innovation Lab director and co-creator of this new kind of insurance.

Recognizing Women’s Needs in Samburu

Since 2017, Carter has led a randomized controlled trial to test the impacts of The BOMA Project’s Rural Entrepreneur Access Project (REAP) paired with a low-cost form of insurance initially designed to cover livestock. REAP provides women who have the least financial means with training and funding to start a business. Most of these businesses are related to livestock or are small shops women operate out of their homes.

However, in Samburu the potential for devastating drought is a constant threat. When their families lose livestock, these new business owners could lose all their hard-won gains.

“The broader Horn of Africa is buffeted by droughts that can destroy more than half of a household’s wealth in just a few months,” said Nathan Jensen, a senior scientist and economist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and a collaborator on the study. “Climate change is only worsening the situation.”

When The BOMA Project began its work in Samburu, Carter suggested pairing REAP with Index-based Livestock Insurance (IBLI), which releases payouts if satellite-based measurements of vegetation predict drought. Payments are timed so people can buy forage and medicines to keep livestock alive. Carter was involved in developing and evaluating IBLI since before it was launched by ILRI in 2010.

Carter’s first thought was that IBLI would be a ready tool to manage risk for REAP participants in Samburu, but since he began testing the paired programs he realized this kind of insurance might not appeal to women. In Samburu, men control the family’s livestock as well as the payments that come from insuring it.

A New Kind of Insurance for the Family

Andrew Hobbs, a University of San Francisco economist who has been involved with this research since 2019, said that when livestock are killed by drought in Samburu, men quickly lose their ability to contribute to family expenses like food or schooling for children. Without their own assets, women have few options to make up the difference.

“A shock like drought often shifts the burden of providing household public goods to women,” said Hobbs. “That often means that women eat less to make sure their children stay fed.”

Insurance is designed for just this circumstance. In the event of hardship, insurance payments can help a family get through until better times. While livestock insurance is not an obvious way for women to make up for lost public goods, a different kind of insurance might be.

“We quickly found that women in these communities are well aware of their indirect exposure to rangeland risk and what it means for their responsibility to feed and care for their families,” said Carter. “Our ah-ha moment came when we realized that recasting insurance to speak to women’s indirect risks and responsibilities would be relatively straightforward.”

Carter and Hobbs came up with the idea of “Family Insurance” that focuses on the family’s collective welfare. The index itself, those satellite measurements of forage that predict drought, would not change, but the insurance could be sold in “Family Units” instead of “Livestock Units.” For women taking part in REAP, this insurance would protect the business assets and savings they have built up over time.

“Family Insurance doesn’t limit how people decide to use the funds,” said Hobbs. “It says you can use this money for livestock, school fees, food or whatever you need.”

Taking Family Insurance to Samburu

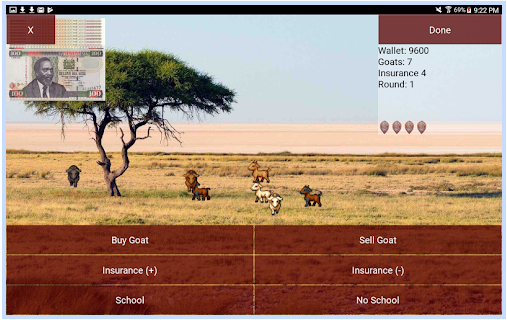

Hobbs first tested the idea of Family Insurance in Samburu in 2019 using SimPastoralist, a tablet-based game he created to simulate ten seasons of buying and selling goats with the additional options to insure them against drought. He tested SimPastoralist with married couples, both playing together and individually. Women who played without their husbands bought twice as much Family Insurance.

Takaful Insurance Africa, the team’s insurance partner in Samburu, found these results striking. They got to work translating what the team learned from SimPastoralist into a real insurance contract, and in 2021 launched the first sales. Family insurance would cost 1,056 Kenyan Shillings (about $9) for a potential insurance payout of 5,600 Kenyan Shillings (about $50). Payouts for drought arrive directly to women’s M-Pesa accounts on their mobile phones.

According to the most recent insurance sales data, the Family Insurance approach led to a 20 percent increase in the number of families who bought insurance. Those who purchased this insurance increased the amount insured by 40 percent.

“These numbers are preliminary and small in terms of statistical significance,” said Carter, “but they are promising and provide a strong foundation for further study.”

“This project takes this idea of livestock insurance and recognizes that it’s for the whole family,” said Elizabeth Katz, a professor of economics at the University of San Francisco currently on leave to serve as director of gender data and research at the Global Center for Gender Equality at Stanford University. While not directly involved in the research in Samburu, she has seen it develop from the beginning.

“This is an example of how noticing gender dynamics can lead to a quite innovative intervention,” Katz added. “As far as I know, nothing has been done along these lines before.”

This work was conducted as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock and was supported by contributors to the CGIAR Trust Fund.

This work was also conducted with funds provided by WEE-DiFine, a BRAC Institute of Governance and Development research initiative that seeks to generate a comprehensive body of evidence that addresses the impact of digital financial services (DFS) on women’s economic empowerment (WEE) and the causal mechanisms between the two by funding rigorous research across South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia.

This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) cooperative agreement 7200AA19LE00004. The contents are the responsibility of the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Markets, Risk and Resilience and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.